Welcome to update #11!

I ended the previous one with ‘First steps: install, test and adjust the clutch and the transmission. Then continue tuning for more horsepower and torque.’ And so I did.

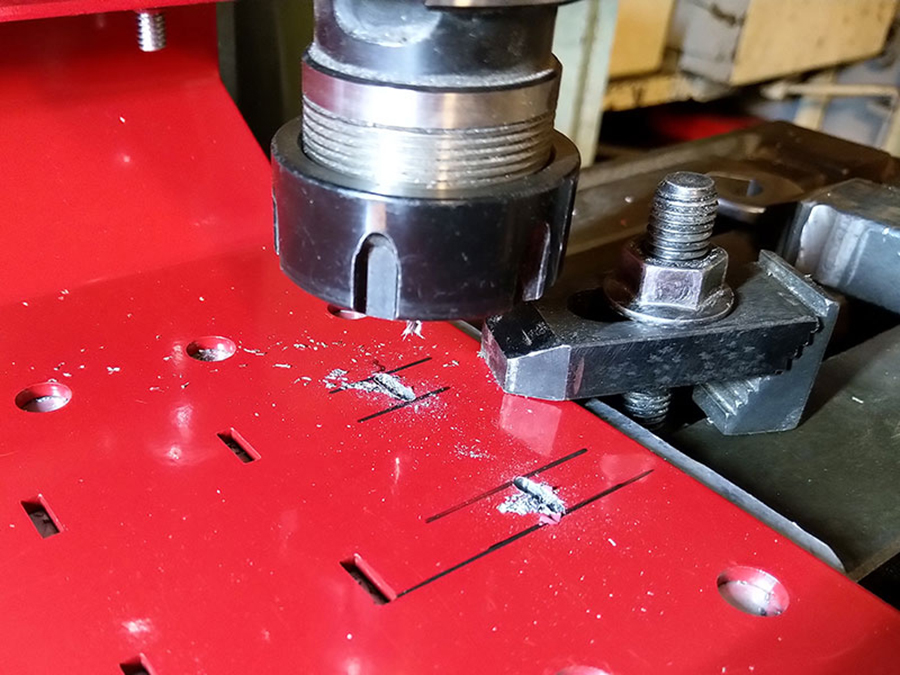

The previous front sprocket was only secured with a single wedge, and we didn’t trust that with the engine’s large torque. On the internet I found SE3416 sprockets with hardened teeth …

… that had to be machined substantial. I lathed the sprocket so it got to the right thickness, Jurriën cut out the center with his wire cutter to fit snug on the output shaft, and Joe Hillers lathed the hardened teeth down from 11.1 mm to 9.525 mm so it fit my 630 dragrace chain.

Quite a lot of post-processing for one sprocket … so I did three.

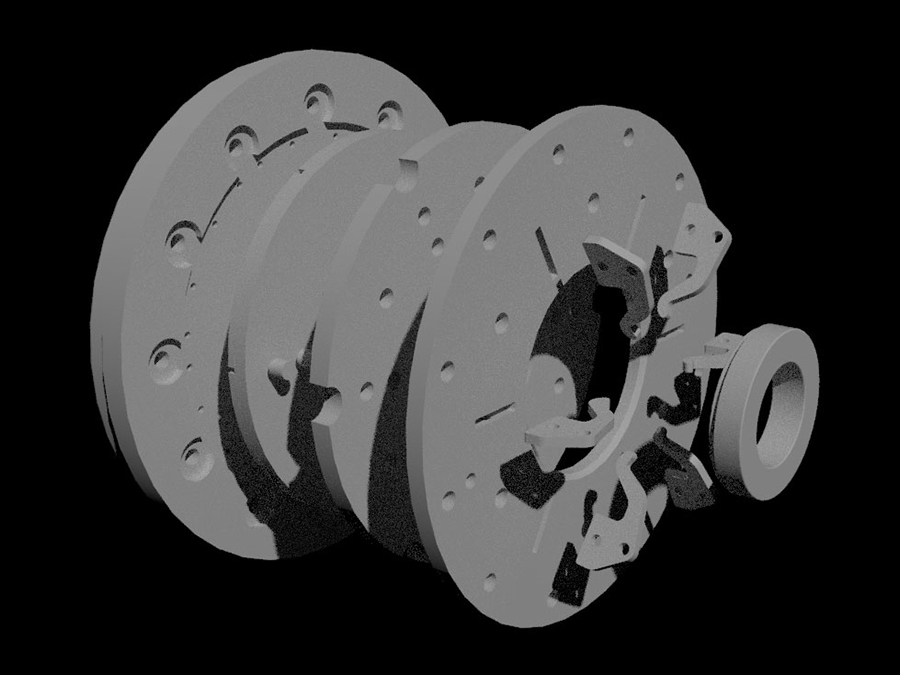

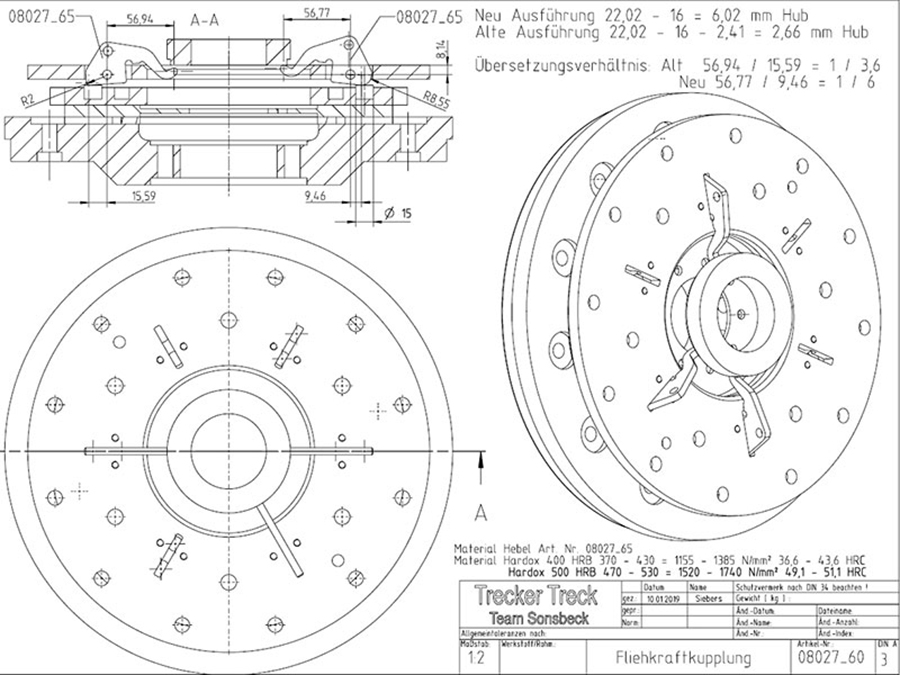

This requires some explanation: until now you pinched the clutch handle to strengthen the connection between the engine and the rear wheel, and you thus helped the centrifugal force of the clutch arms to close the clutch even more. That is not ideal because it’s opposite to the usage of a normal car or motorcycle clutch: here you loosen the connection between engine and wheels.

In emergency situations this can lead to a wrong reflex: you strengthen the connection by retracting the clutch lever, which you don’t want in such a case.

In the new version you break the connection between engine and rear wheel. This is much safer because the clutch now doesn’t add to the centrifugal forces but rather reduces the connection between engine and rear wheel.

January 8, 2019: first test day of the new clutch, pressure group and transmission. On the right: Josef Siebers, the brain behind the new clutch concept. We didn’t test on the dyno because we wanted to see the rear wheel spin freely without counter-pressure from the roll. And had ample possibilities to adjust the clutch: spring strength and pre-tension, play of the clutch plate and centrifugal weight.

Unfortunately, after the first test the tips of the arms were already completely worn out, from a curve to a surface of no less than 6.5 mm wide. The material used, S700MC, was not hard enough. Difficult to find a steel that is both hard (so: durable) but not so hard that it becomes brittle and snaps. After consultation with the supplier, we chose Hardox 500, which is more than three times as hard but nevertheless not brittle.

Unfortunately, after the first test the tips of the arms were already completely worn out, from a curve to a surface of no less than 6.5 mm wide. The material used, S700MC, was not hard enough. Difficult to find a steel that is both hard (so: durable) but not so hard that it becomes brittle and snaps. After consultation with the supplier, we chose Hardox 500, which is more than three times as hard but nevertheless not brittle.

With new, tougher arms and fixed axles we tested on February 25th. During this test we didn’t understand why so much centrifugal weight was needed: perhaps the clutch plate was not completely flat anymore and therefore had little contact? We also saw imbalance in the rear wheel. So I took it all apart again.

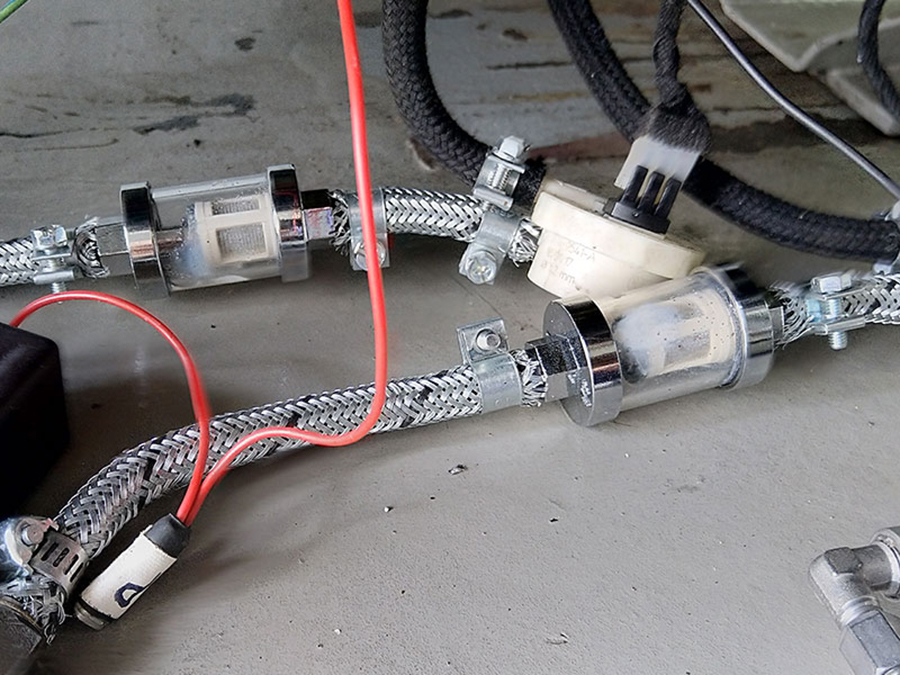

May 2019, I took a closer look at the water-methanol injection system: when purging (= pumping out) the fluid it turned out that there were small black rubber residues in the collection bottles. Because methanol is a very aggressive substance, some rubber was probably dissolved from the hoses over time, although these should be able to withstand it. Pollution can clog the nozzles of the system and that is a bad and unwanted thing.

May 2019, I took a closer look at the water-methanol injection system: when purging (= pumping out) the fluid it turned out that there were small black rubber residues in the collection bottles. Because methanol is a very aggressive substance, some rubber was probably dissolved from the hoses over time, although these should be able to withstand it. Pollution can clog the nozzles of the system and that is a bad and unwanted thing.

Mid-August: two test days. After so many innovations and improvements, the ‘hopes were high’. Unfortunately the first day was one full of setbacks: leakage in the water-methanol system, the umpteenth killed lambda sensor, and clutch slip; a problem the previous clutch version did not have. Solution: heavier centrifugal weights.

So let’s lathe centrifugal weights! Not a big challenge you’d think …

Next step: because we never got above 1.2 bar the turbo pressure, we decided to use a compressor to put air pressure on both wastegates in the next test. As a result, they would remain permanently closed and thus lead the exhaust pressure to the turbos, and not to the exhaust. This should increase the inlet pressure, and with it the fuel consumption, and therefore the horsepower.

The pressure test of the hoses and the solenoid also took two stages: after replacing a hose, the system was 100% gas-tight.

Unlike a gasoline or methanol leak, a small NOS leak is not that dangerous; it can even get you in a good mood for a short time. ;)

But that fun is quickly over as the gas is hard to get and quite expensive.

“That’s how we do it!”

This concept worked. With a positive effect and — of course — a negative one. Positive: we now know that we have twice as high outlet pressure than we have inlet pressure, and we can conclude that the turbos supply enough pressure (= psi) but not enough flow (= quantity), probably because the turbines of the turbos are too small for my configuration.

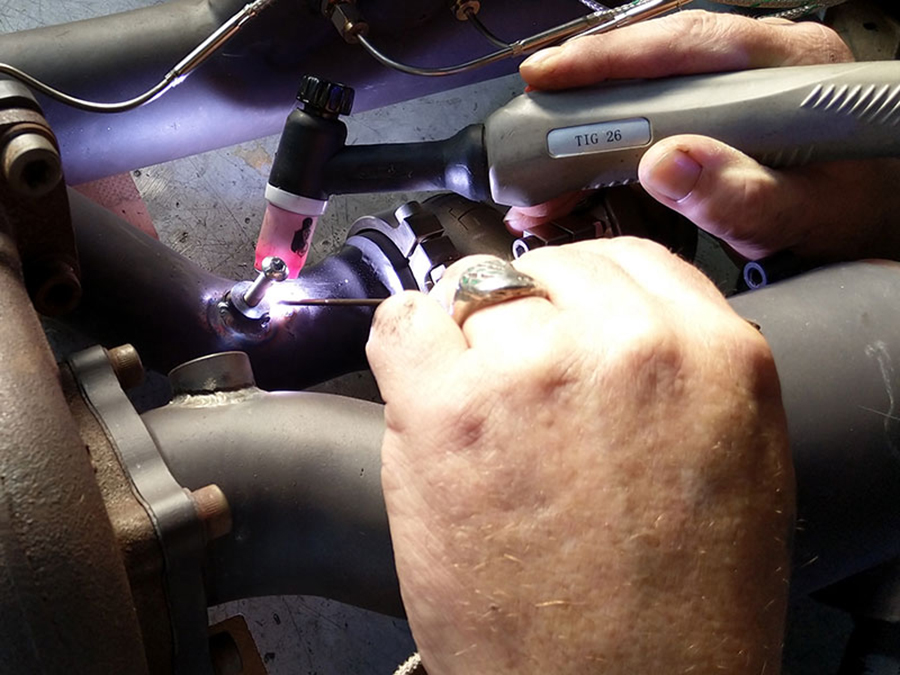

Negative: the 32 psi the boost activated the engine managements boost safety system, resulting in a so-called ‘backfire’ (= explosion) in the intake manifold that shook the entire test area; a ‘worst nightmare’ for me because this could have ruptured the intake manifold, and worse.

But again two positive conclusions:

1. that didn’t happen, and 2. we’re still alive.

It was clear that we wouldn’t activate the nitrous oxide system that day, despite the fact that drag racer Aldert Tjoelker had come specifically for that purpose from his hometown Drachten all the way to Germany. Here he poses next to his huge NOS filling station.

It was clear that we wouldn’t activate the nitrous oxide system that day, despite the fact that drag racer Aldert Tjoelker had come specifically for that purpose from his hometown Drachten all the way to Germany. Here he poses next to his huge NOS filling station.

Still: thumbs up, as we had a nice couple of beers together.

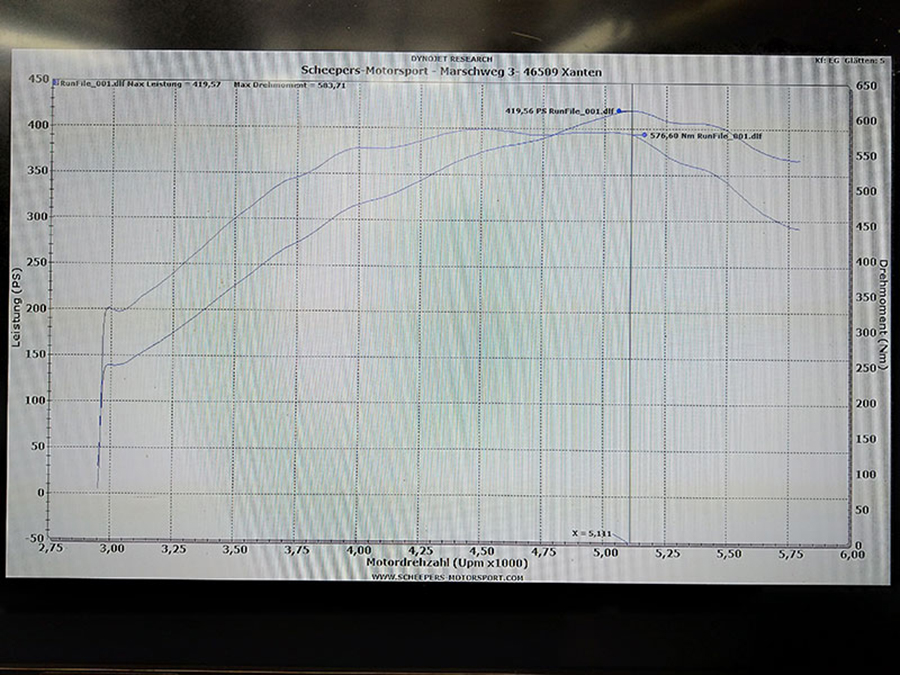

And now? Like always: just continue. Enlarging the turbine housings, thus hoping and expecting to generate more flow, and subsequently more horsepower. Because 419 rear-wheel horsepower is nice … but not enough.

It’s just like the eponymous main character in the movie ‘Carrie’: just never give up. ;)

To be continued: here!