February 13, 2016: positive thoughts on what could be our final testing day. With a little bit of luck the V8 would show its real potential. Followed by disassembling, paintjob and hitting the road.

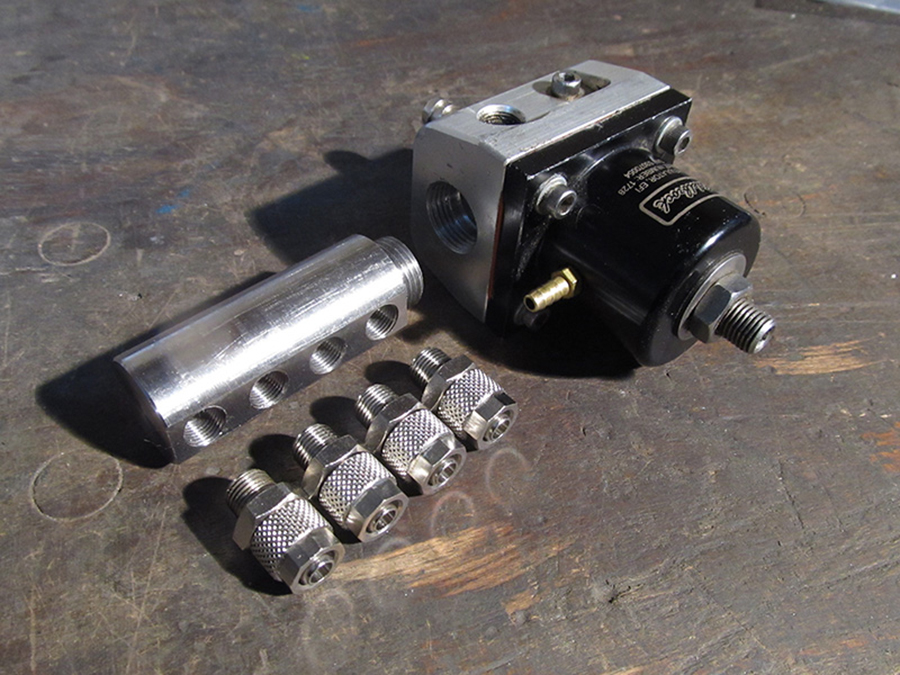

To favor the gods, I’d purchased three professional gas masks, partly because today the water-methanol system would be used. And that’s harmful stuff.

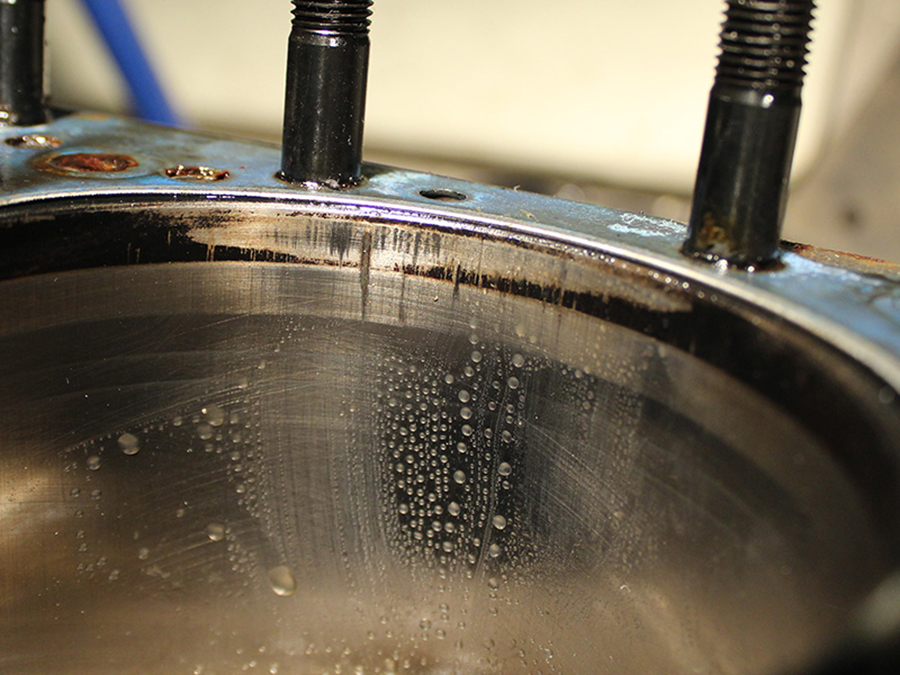

Unfortunately: no way. The oil level was too high and cloudy. So we heated up the engine, drained the oil, replaced the oil filter, and put fresh oil in. There appeared to be coolant in the oil, and that’s not a good sign at all.

Tja. De motor bleek ziek. Verder testen had geen zin.

Well. The engine was sick. Further testing didn’t make sense.

We drew the following conclusions:

1. The cause of the coolant leakage must be found and remedied.

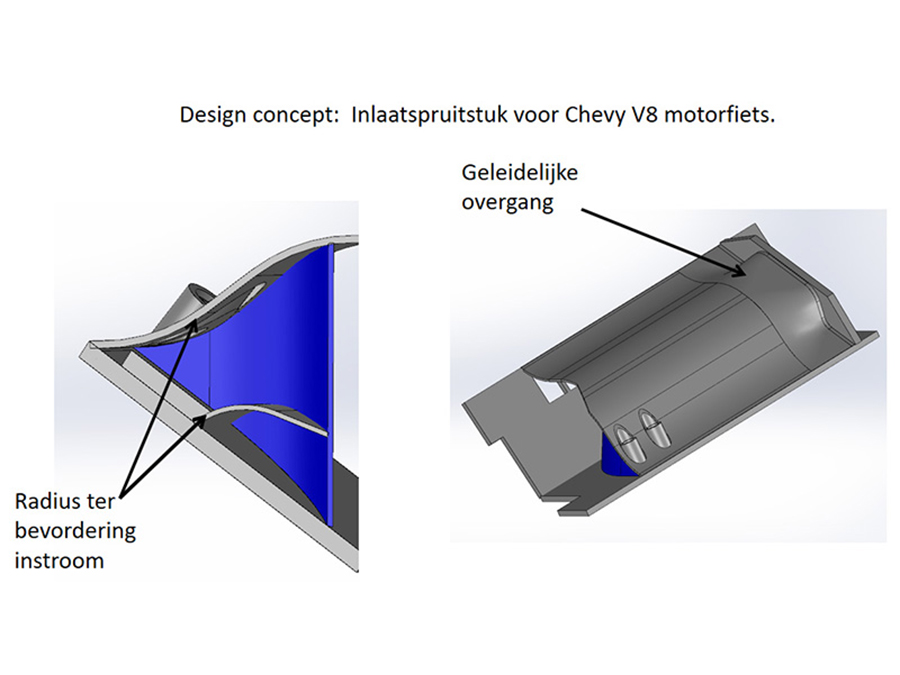

2. The engine does not get enough air because the flow of the intake manifold is not good. Not enough air means not enough gas means not enough power. And 350 rear wheel hp is not enough power, that’s very clear.

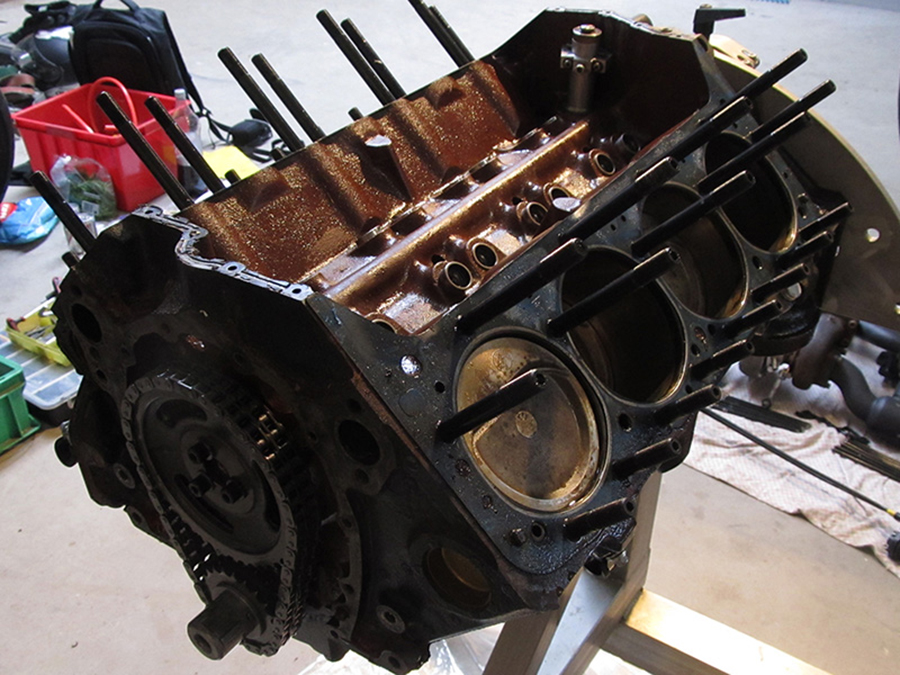

So what do you do? You disassemble the whole bunch. More then ever before.

The coolant leakage was partly due to the fact that the 2K filler I used was not glycol resistant (see update #8), and partly that the intake gasked was too rigid for my aluminum intake manifold. Now that I switch from FelPro # 90314-2 (‘Standard’) to FelPro # 1205 (‘Performance’) that problem is probably fixed.

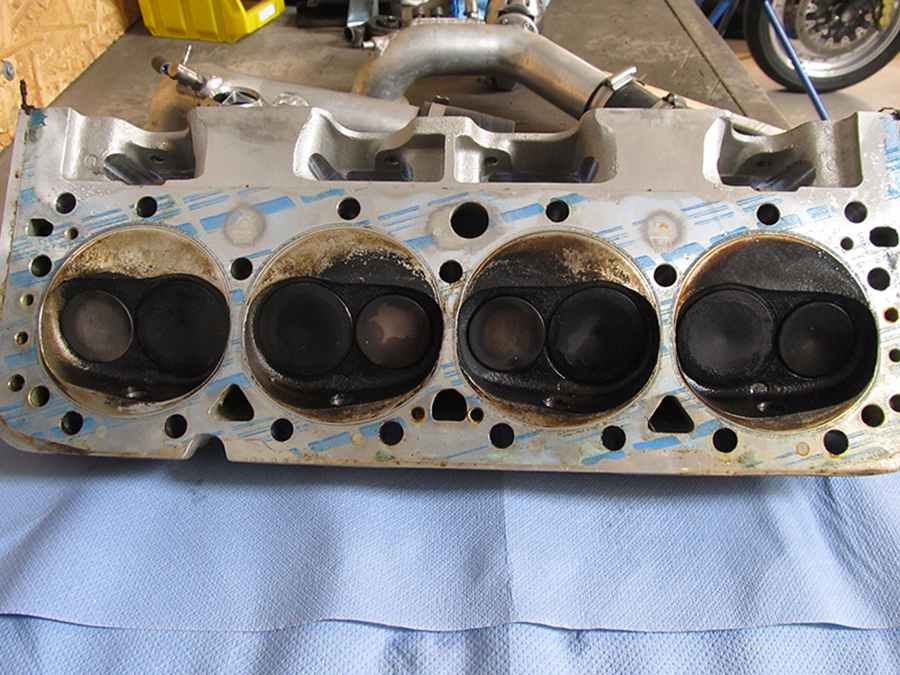

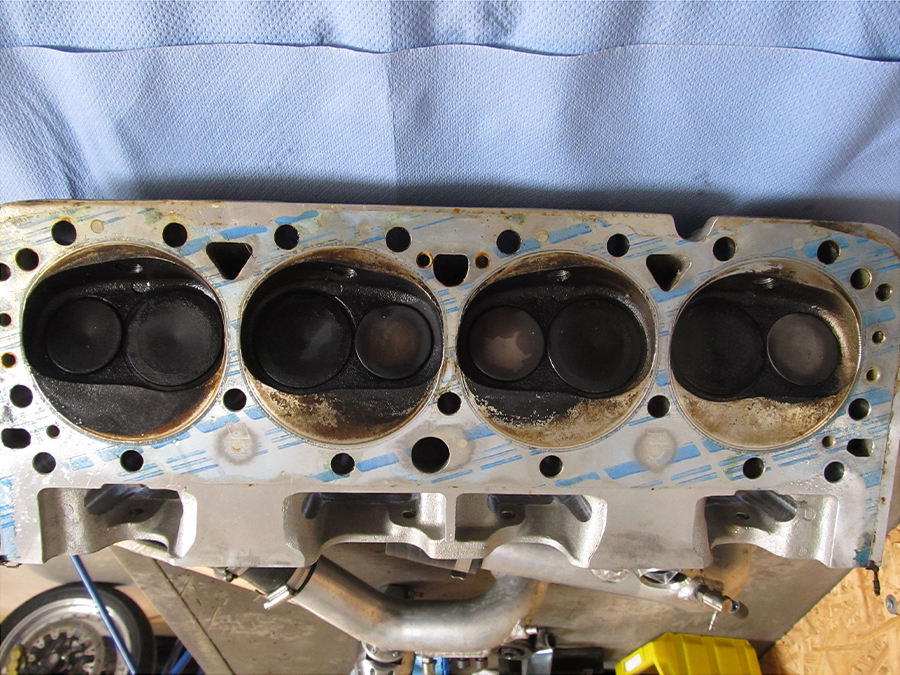

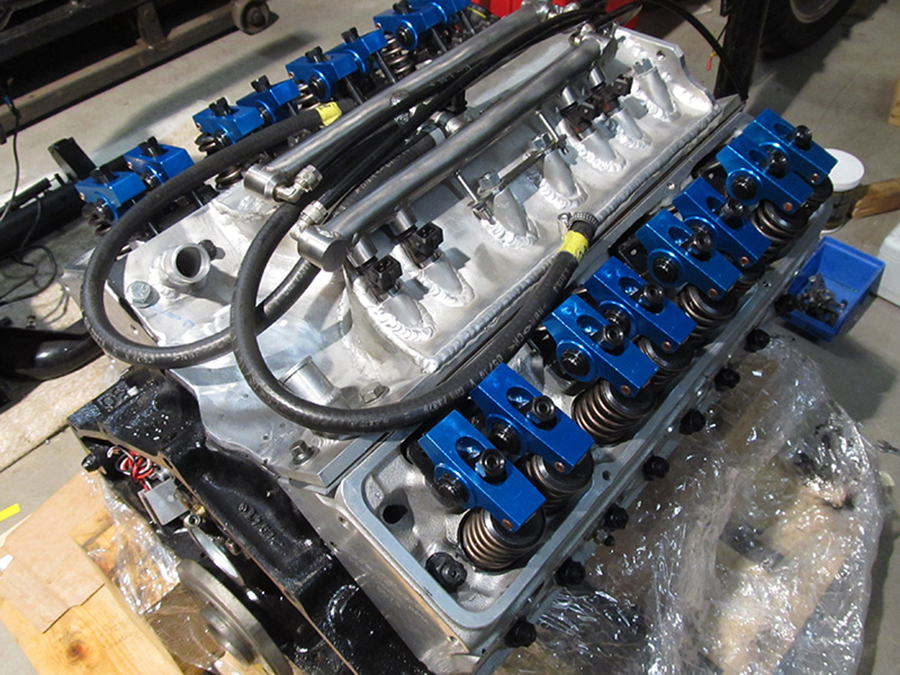

The heads clearly showed that the air flow in the intake manifold was far from ideal. From left to right you see the valves and the combustion chamber getting more and more black: on the left, where the air enters, the air-gasoline mixture is too lean, so little carbon but temperaturs too high.

On the right, at the back of the manifold, the air-gasoline mixture is too rich: cooler but much more carbon deposit.

And in between it’s good. More or less. So: not good at all.

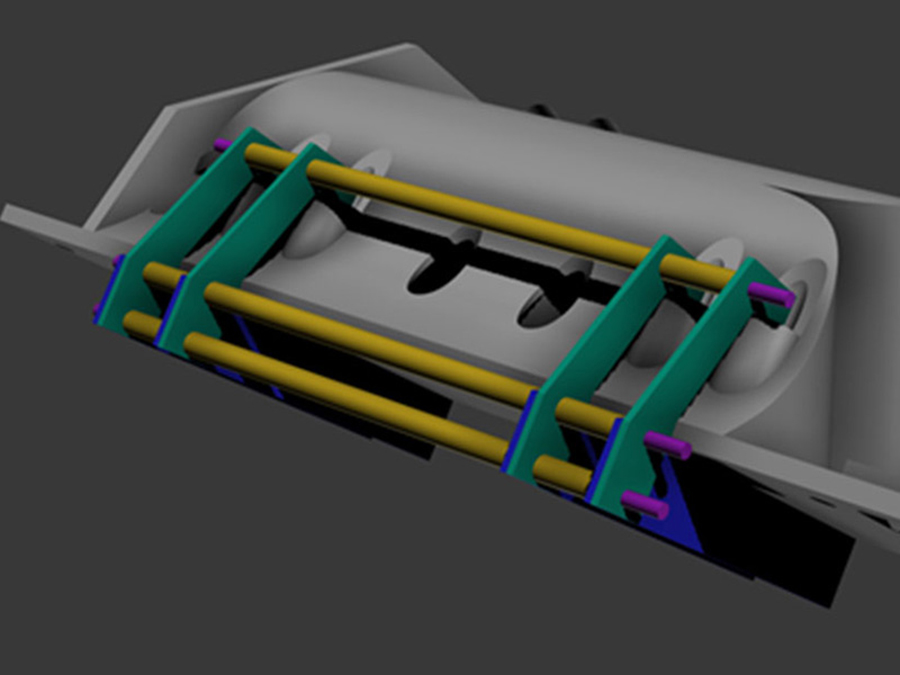

That same month Michel Verrips (r) visited the scene of the crime. He has a lot of experience in engine tuning, especially in designing intake manifolds.

The challange is getting as much air flow as possible in the limited space between engine and tank.

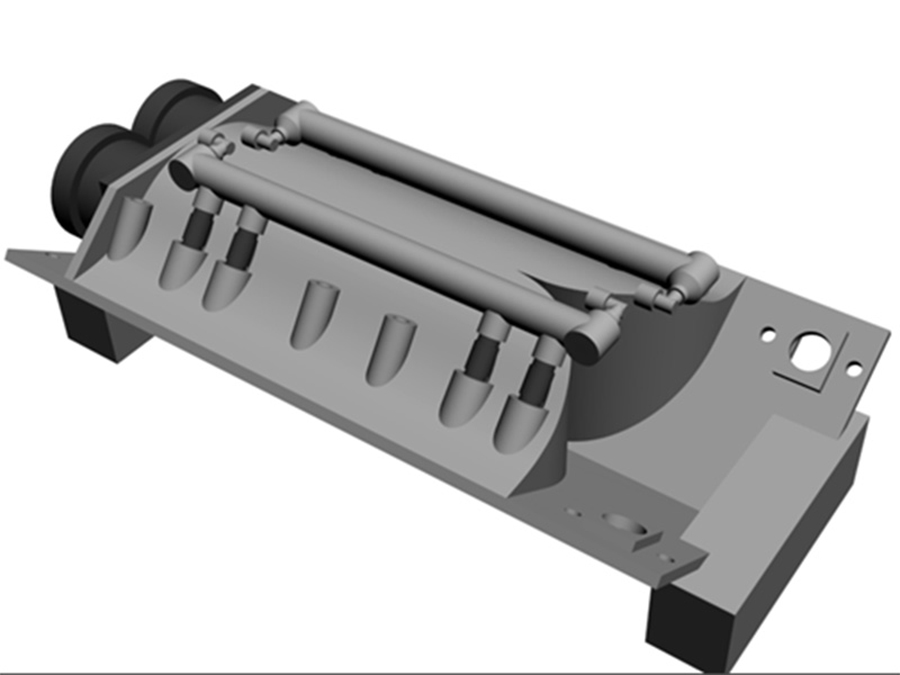

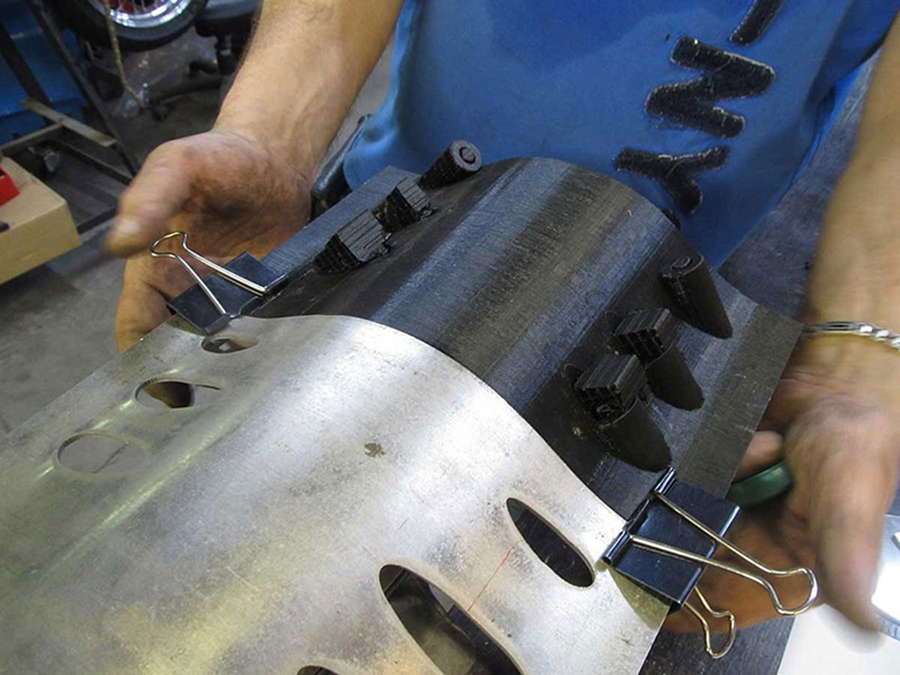

This is what the original intake manifold looked like, just before it was welded (long ago). The square tubing provided a bad flow. ‘No worries’, I was told ten years ago, ‘your huge turbos will press the air wherever it has to go, no matter size or design of the manifold.’ This turned out to be true, but no further than 350 hp. And we want to get past that, and a lot.

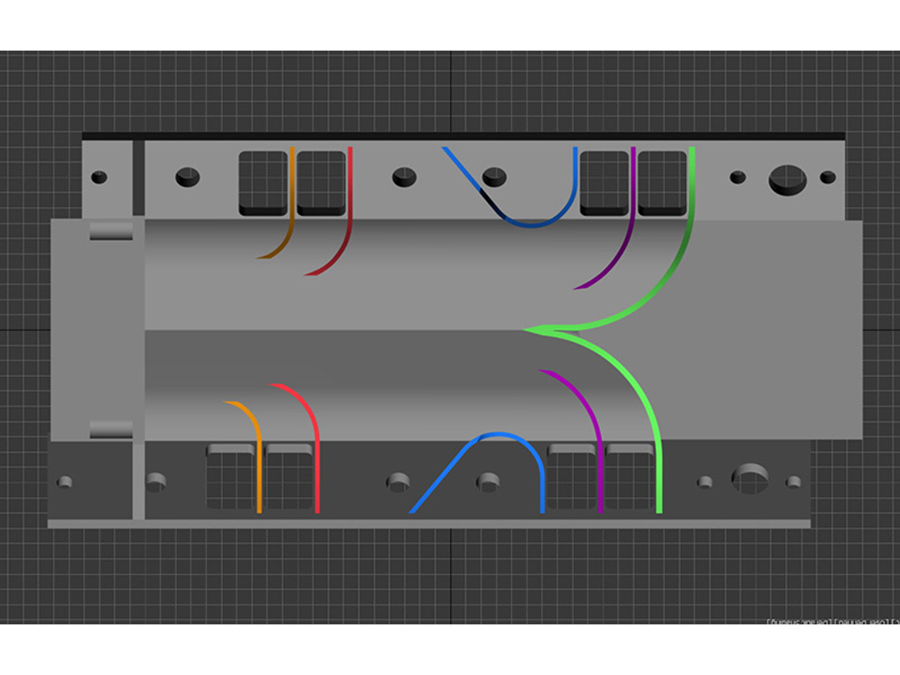

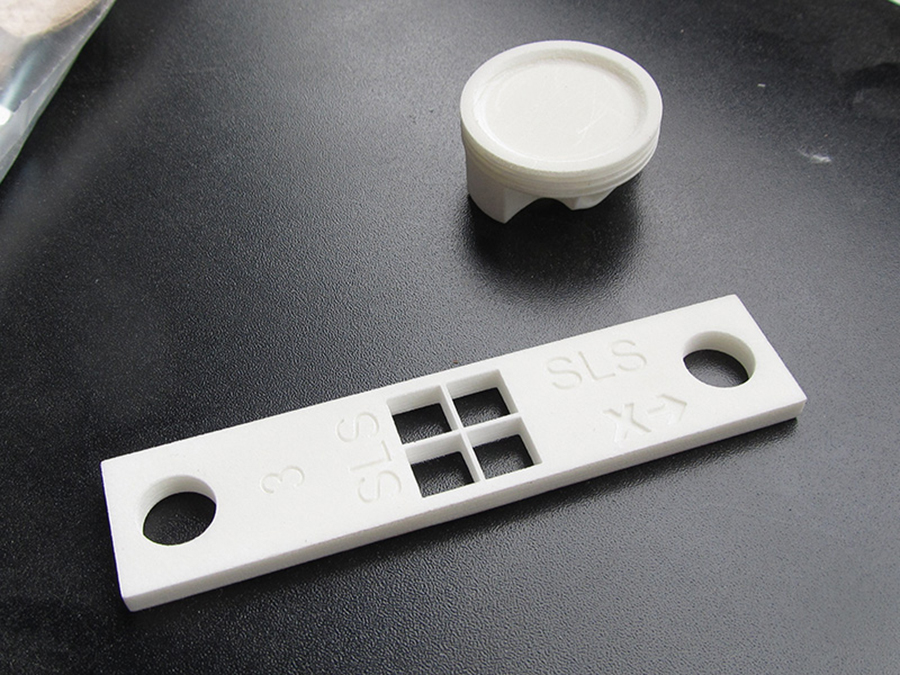

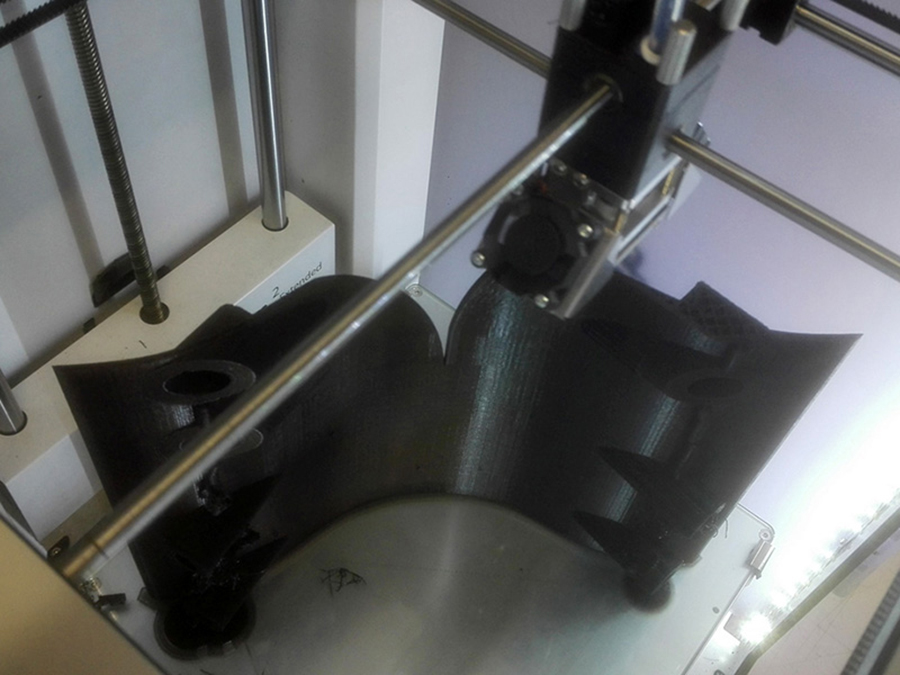

I came in contact with Peter Schneider: he installs and repairs professional 3D printers. We discussed the possibilities to print my new intake manifold instead of constructing it. This would save a lot time: directly from computer model to end product. No welding and therefore no deformation due to the input of heat. Sounds ideal.

I came in contact with Peter Schneider: he installs and repairs professional 3D printers. We discussed the possibilities to print my new intake manifold instead of constructing it. This would save a lot time: directly from computer model to end product. No welding and therefore no deformation due to the input of heat. Sounds ideal.

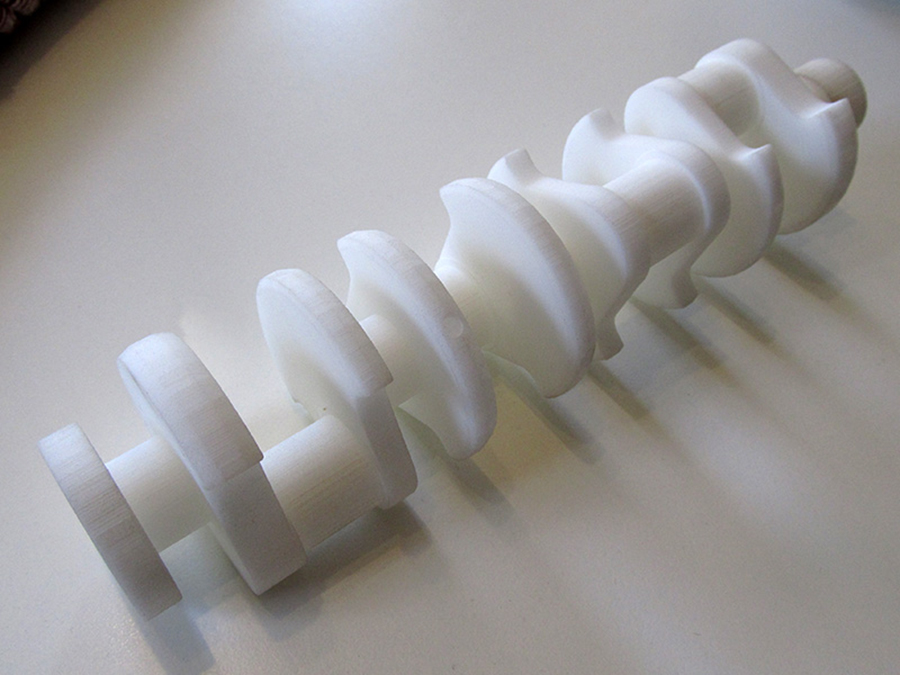

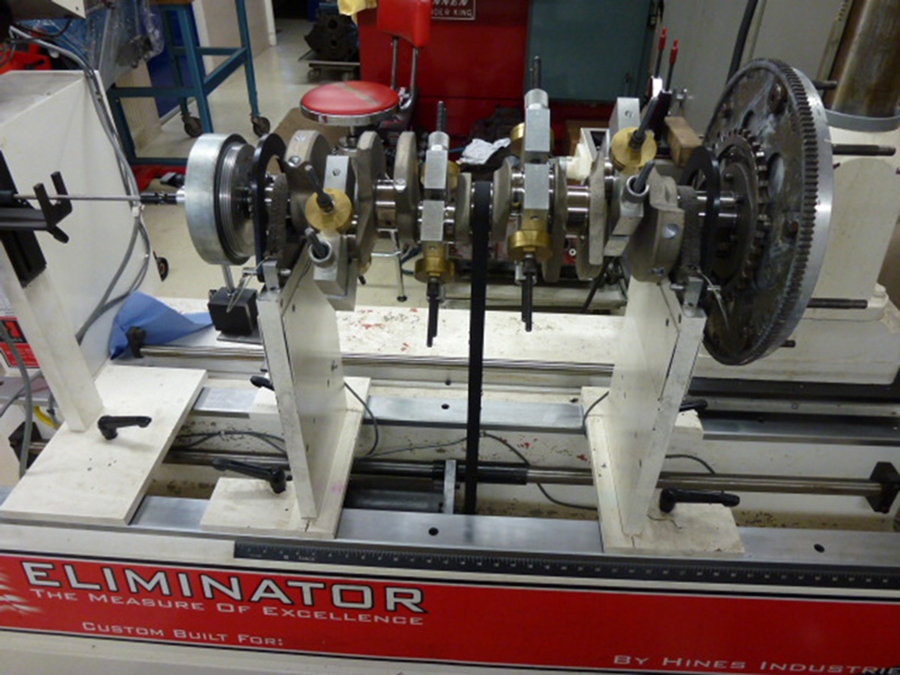

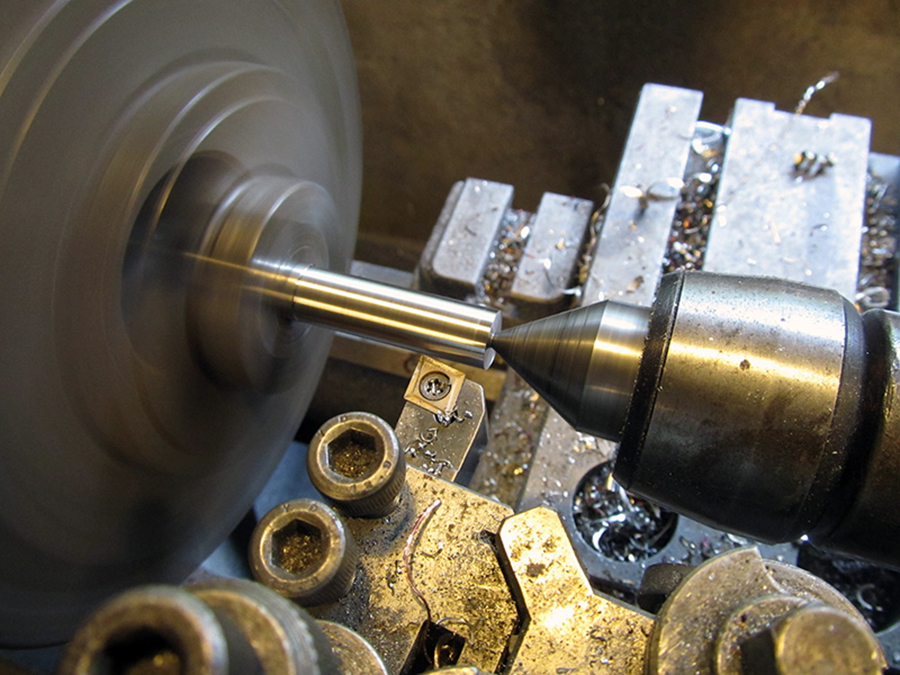

… but also complex ones, like this crankshaft.

Unfortunately, there was too much uncertainty about strength, shrinkage, gasoline-, oil-, coolant- and pressure resistance of the available plastics.

Nowadays printing (‘sintering’) in aluminum and stainless steel is also possible, but not with Peters printer. And they are a bit ‘above budget’: 8,000 (aluminum) and 30,000 Euro (stainless steel). All in all too risky and far too expensive. But this technique is, of course, the future.

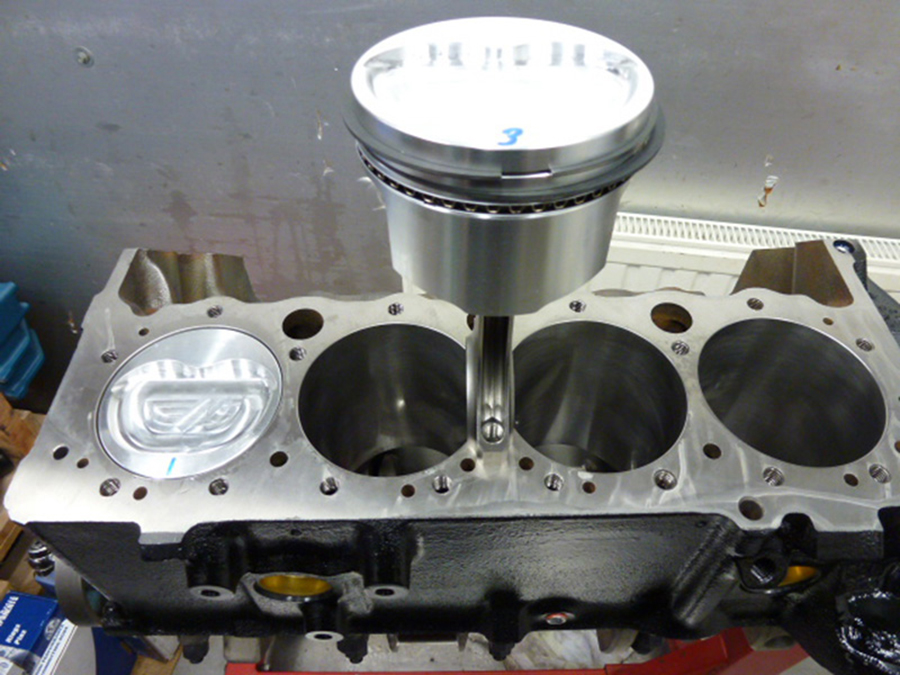

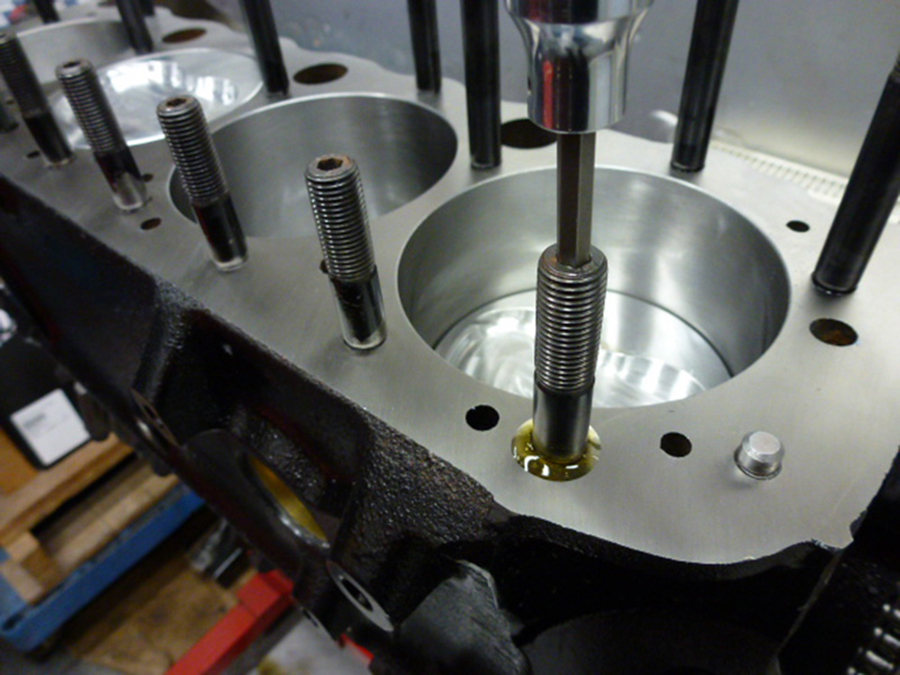

I prayed that the rest of the engine was salvable. That wasn’t the case: a complete overhaul was inevitable. The coolant had pushed away the oil film of all the rotating parts, so metal scratched on metal.

German V8 expert Jürgen examined the patient. He promised to make a quote but ended up with a lot of lame excuses. In Germany they call that ‘Zeitverschwendung’…

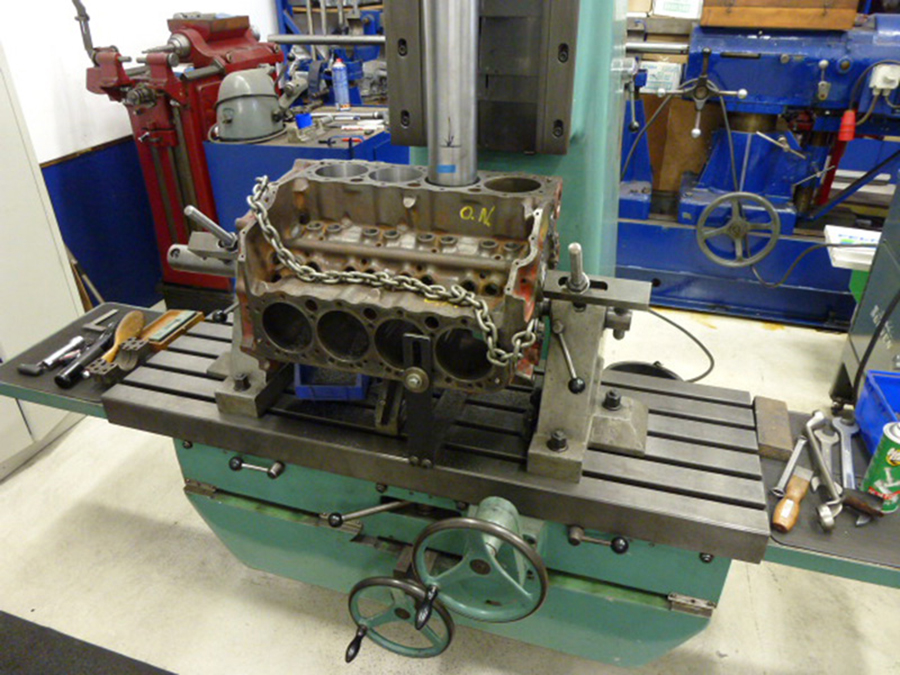

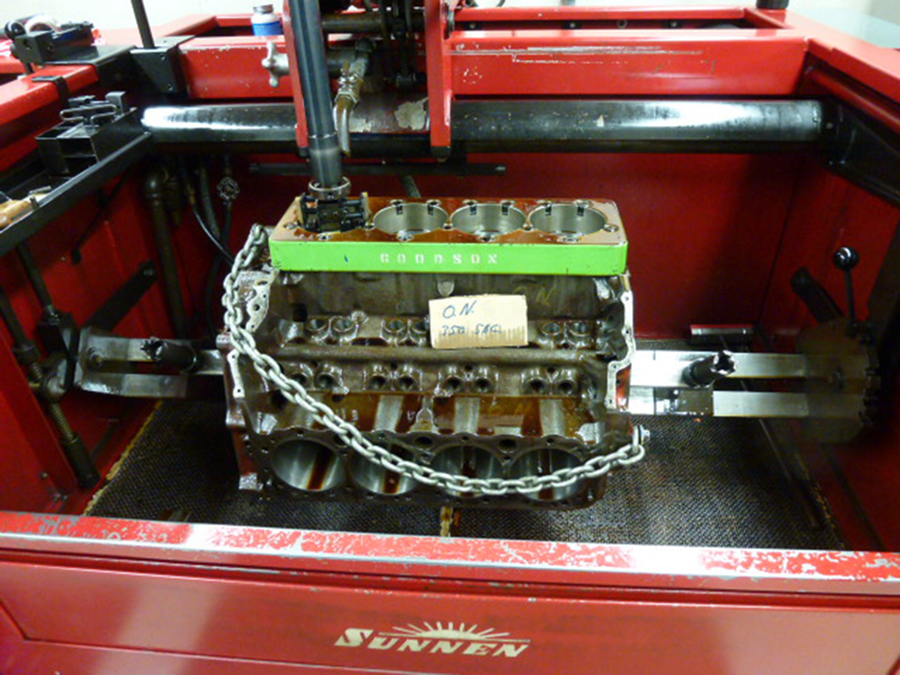

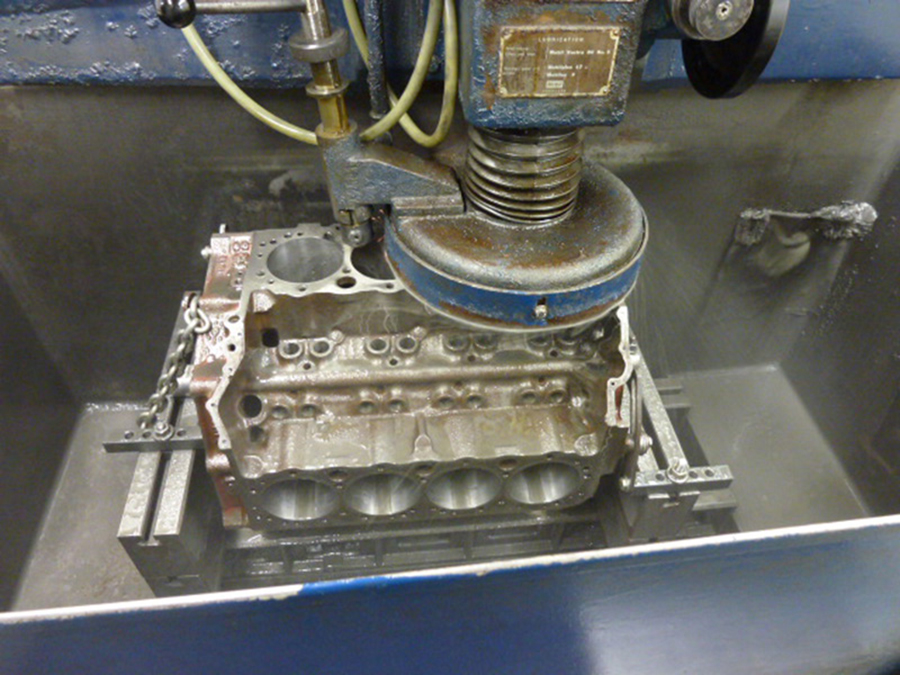

Ronnie Spijker guided me to Jacco Griekspoor. His company, Jacco Cars & Parts (“no website, don’t need one”) is all about overhauling US engines. We immediately had a connection: V8, but also six-cylinder bikes (he Kawa, me Honda), and Münch Mammut. My engine would be in good hands.

Sadly not even overhauling was possible: unfortunately the engine could not be saved. Some cylinder walls were so scratched that the wall thickness would be unacceptably thin with oversized pistons.

Talking about ‘unfortunately’: the crankshaft couldn’t be saved either. And Jacco advised other (heavier) connecting rods. And yes, while we’re at it, let’s put a more aggressive camshaft in. A serious upgrade, and financial a very painful one.

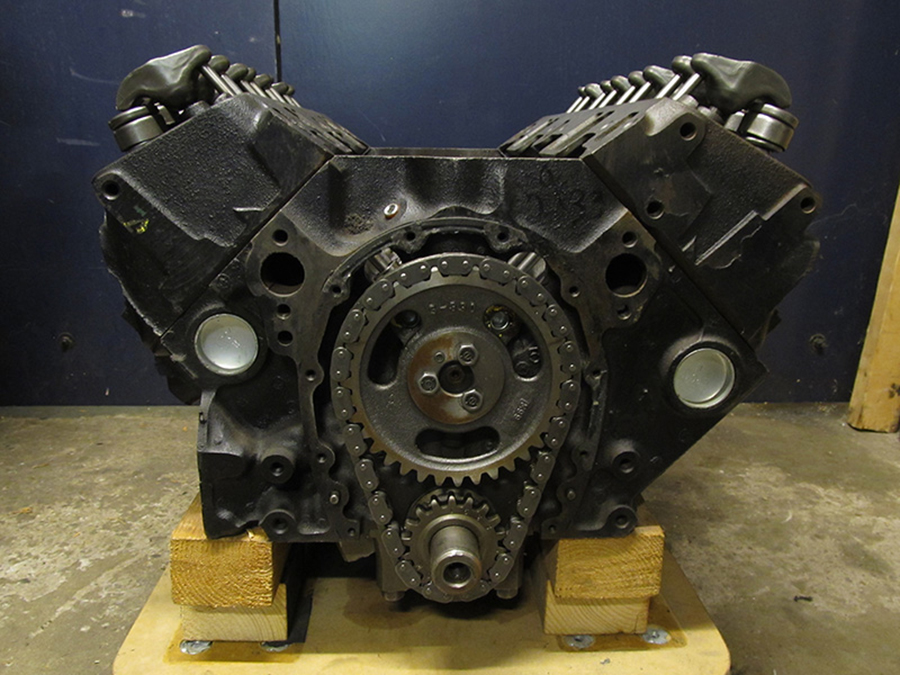

Rebuilding is always rewarding. Here you see the nice painted front plate (by KustomBart).

Rebuilding is always rewarding. Here you see the nice painted front plate (by KustomBart).

Less satisfying is that, apart from this plate, the looks of the bike didn’t change a bit. And at the same time that was my intention. Are you still with me? :)

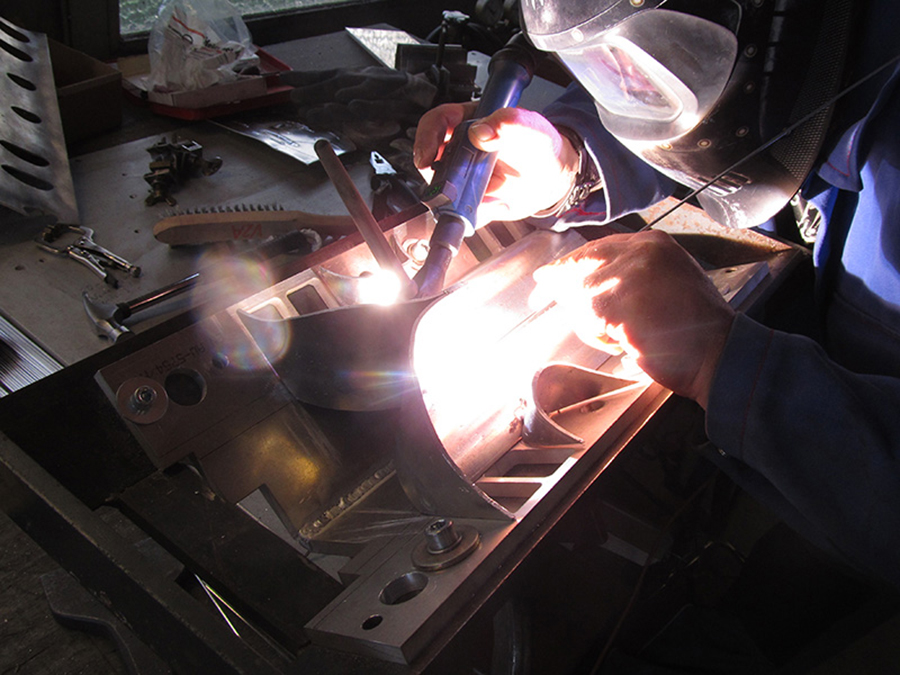

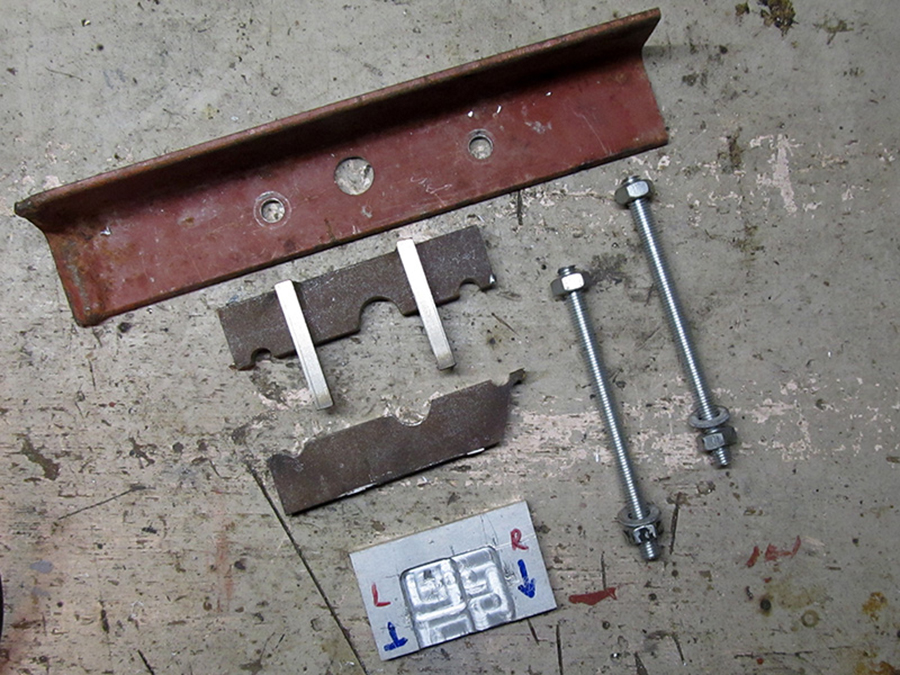

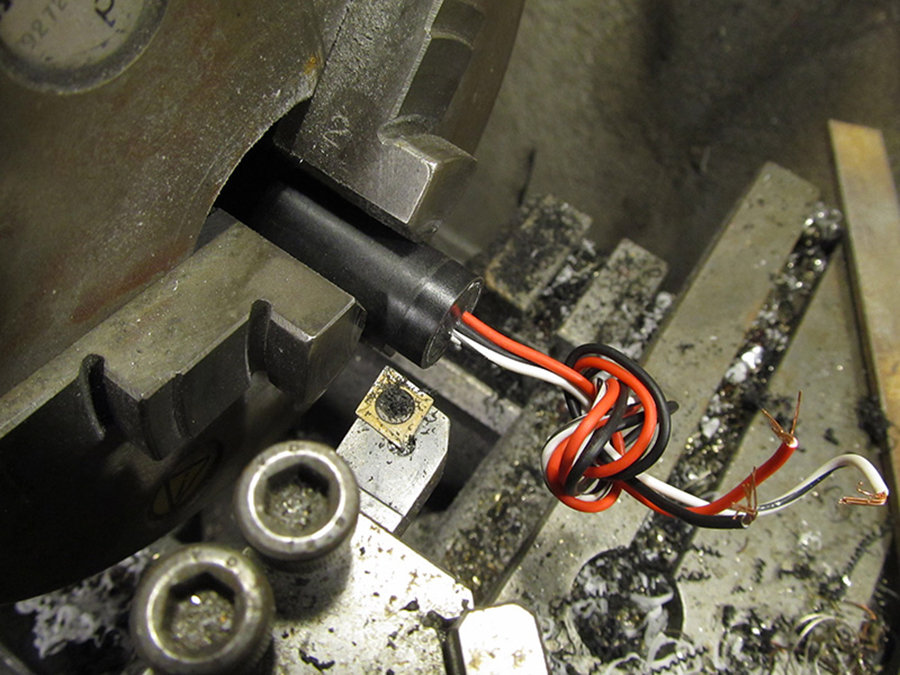

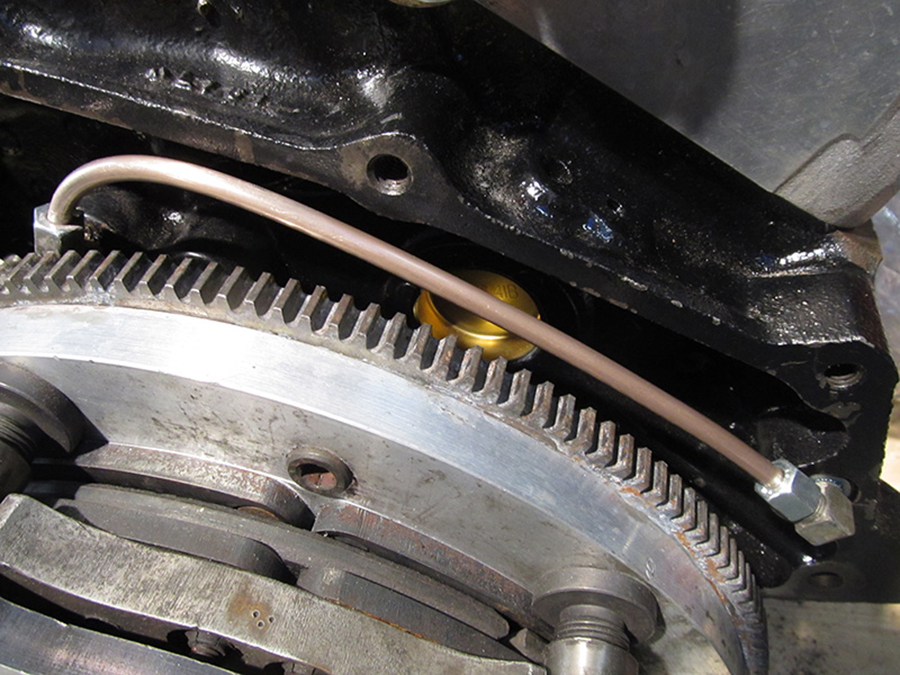

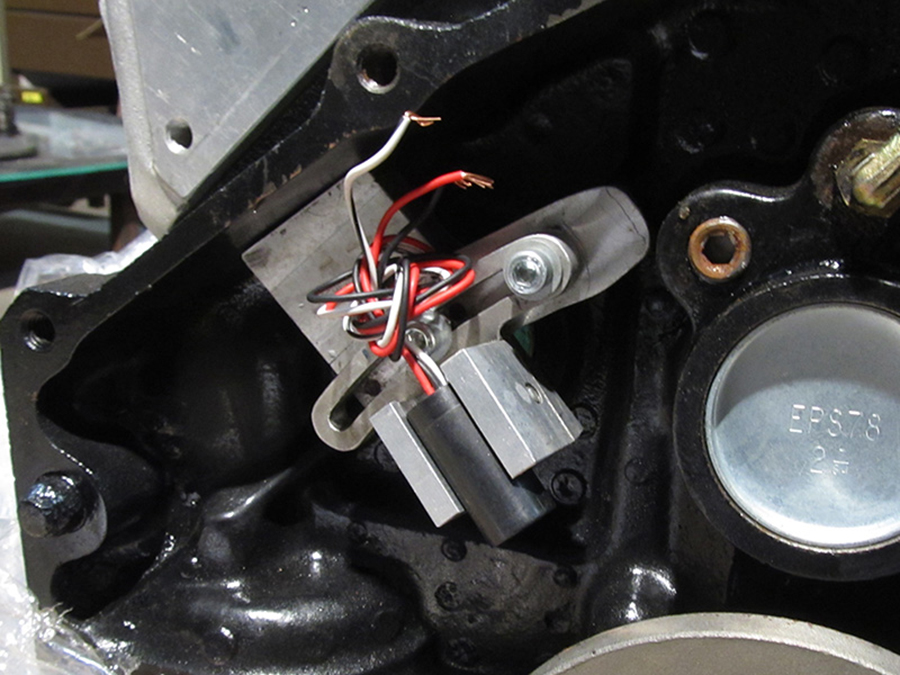

In each of the eight exhaust tubes I drilled a hole for a so-called EGT (Exhaust Gas Temperature) connection. There will be eight new temperature sensors: the exhaust gas temperature gives important information about the combustion (too rich, too poor or good), and that of course it is of the utmost importance for engine tuning.

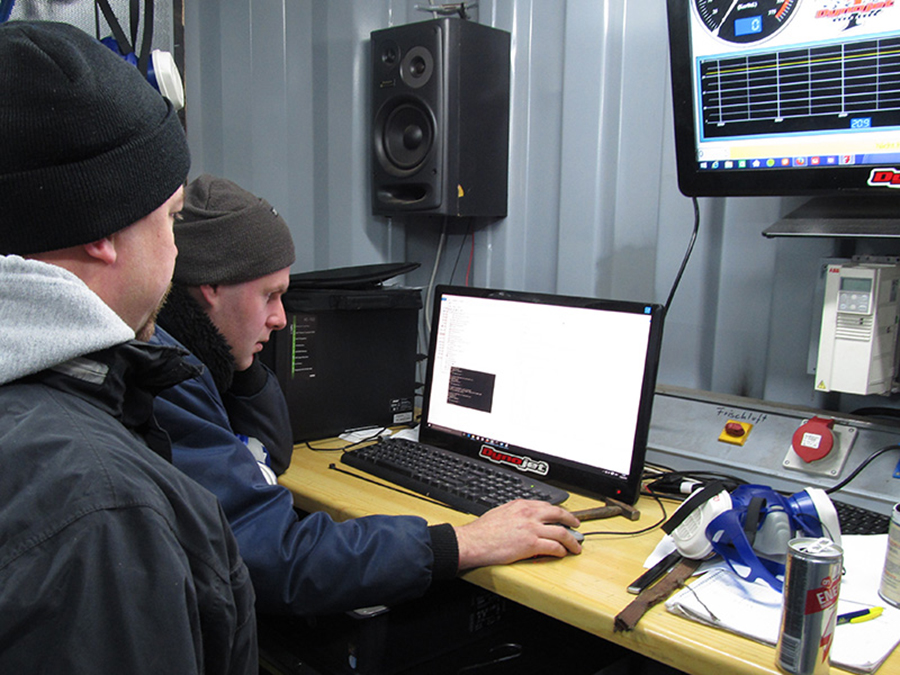

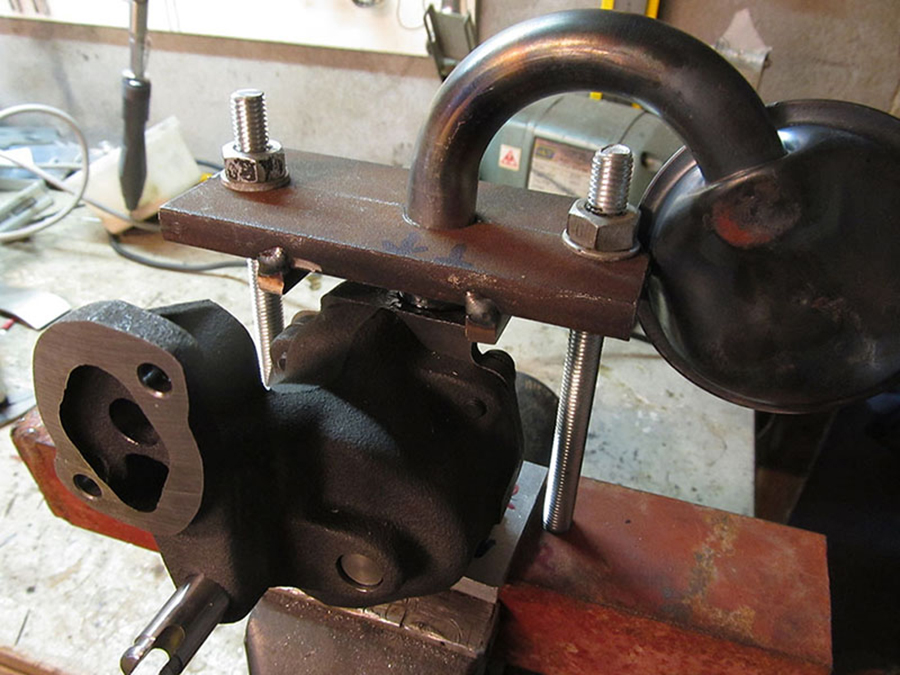

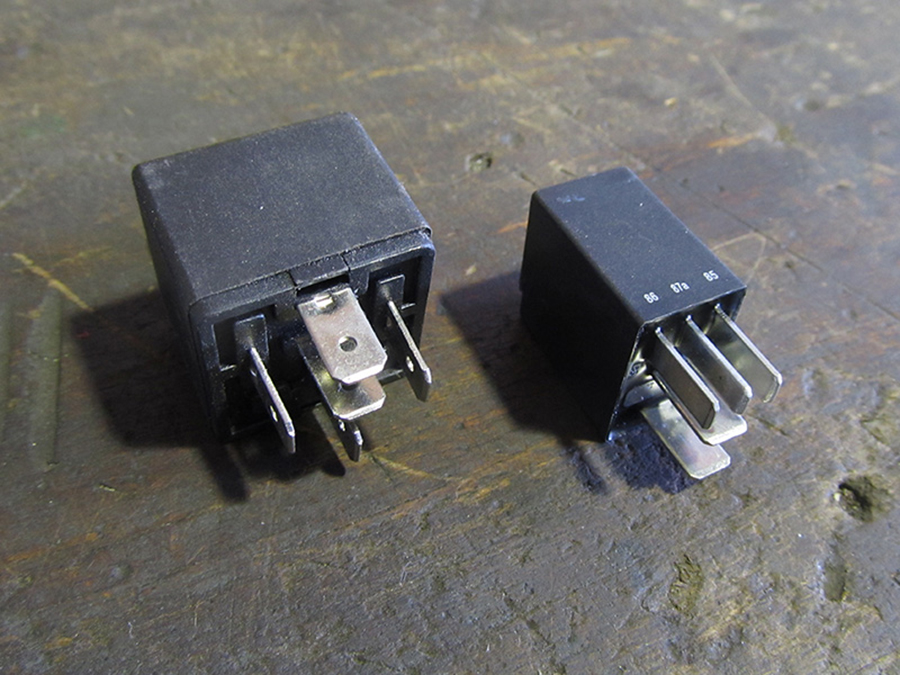

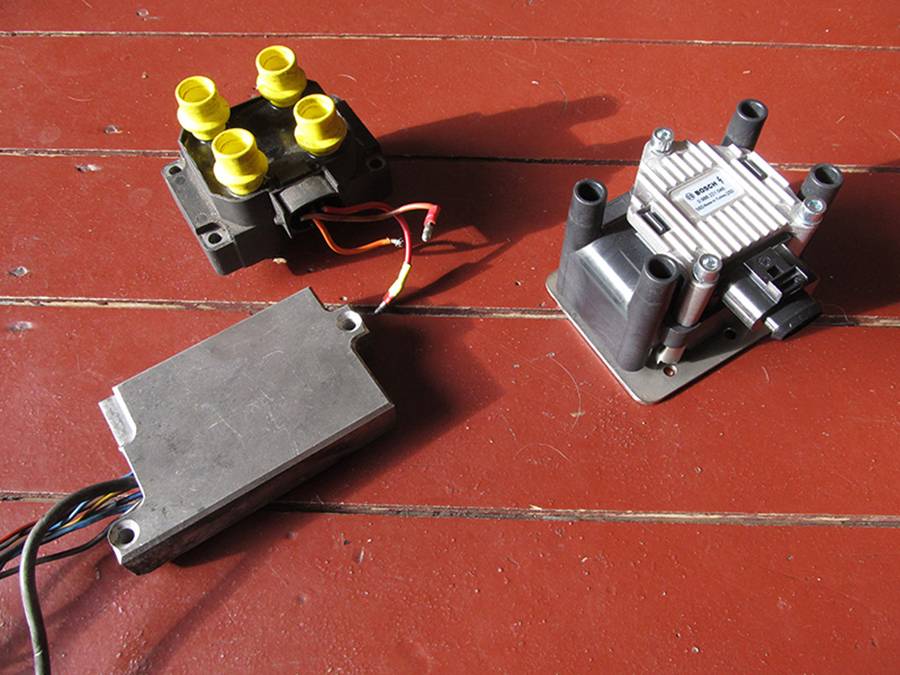

Always a nice activity: problem solving at Holl, this time with Remco.

Always a nice activity: problem solving at Holl, this time with Remco.

I made a great deal with Kevin from KB USA Parts: he checked the engine and resold it to a customer. Everybody happy.

And that is fun. As you can see.

And that is fun. As you can see.

“Okay, and now what?”

– “A bit of wiring, a bit of Dyno testing, a box of spray cans, that’s all.”

“Really…?”

– “No, of course not!”

See you next year! … here :)